Protecting bat habitat in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness

September 5, 2025-

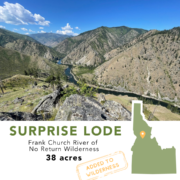

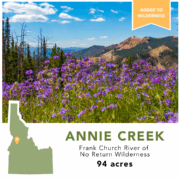

Given that many of the private wilderness inholdings that we work to protect are old mining claims, it’s not uncommon to find open mine shafts or adits, the horizontal passages used to access underground mines, on them. When we do, it is important to close them off before the property becomes public lands to ensure public safety. Our staff recently visited our Annie Creek project in Idaho’s Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, which we acquired in last year in partnership with the Payette Land Trust, to close two open adits on the property. But how that’s done has a big impact on one of wilderness’s little thought of, but most important species: bats.

There are at least 13 species of bats in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. A single little brown bat, one of the most common species found there, can consume over 1,200 mosquito-sized insects in just one hour. If you’ve ever tried to put up a tent or cook your dinner while camping in the thick of mosquito season, that alone may be enough to convince you of the importance of bats in the wilderness. But bats are also critical for healthy forests, protecting young trees from insect damage. Researchers have found that forest where bats are present have three times less insects and five times less defoliation of young trees than forests without bats. When young saplings are defoliated, having their leaves eaten by insects, they are more vulnerable to stressors like drought and fungal diseases. Beyond playing an important pest control role in forests, bats eat enough pests so save more than $3 billion a year in crop damage and pesticide costs across US agricultural production. Bats are also important pollinators. But due to disease and habitat loss, bat populations are in decline across the country.

While many species of bats actually roost in trees, habitat like caves and abandoned mines are important for reproduction and raising their young. So when it comes to closing off mine adits on the Trust’s properties, we make sure that they are still accessible to bats. Sometimes, when the property is easily accessible, that means installing steel bars or grates across the opening. In Colorado, the Division of Reclamation, Mining, & Safety has a program to help install these grates, but no such program exists in Idaho. In the case of Annie Creek, where steel grates would be too heavy to hike in, we had custom cable nets fabricated to stretch across the roughly 5×7’ opening and bolt into the rocks surrounding them. Quarter inch cables are used to create a six-inch square mesh, ensuring bats can easily fly through them.

Our staff were joined by two of our local USFS partners, and we were able to hike in all the materials and install both nets in just one day, instead of the two we had anticipated it would take. This kind of stewardship and restoration is an important part of our work, both to ensure that properties are cared for after we acquire them, and to return them to their wilderness character and mitigate any safety hazards before they become wilderness and public lands.