January 5, 2024-

The Wilderness Land Trust is delighted to be partnering with Pitkin County, CO in a landmark conservation deal to protect the 650-acre Snowmass Falls Ranch. For more information on the project, see the County announcement below.

Pitkin County poised to make historic open space purchase

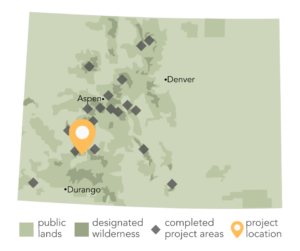

PITKIN COUNTY, CO – A $34 million open space acquisition that will preserve 650 stunning acres in the upper Snowmass Creek Valley, bounded on three sides by the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness Area, will go to Pitkin County commissioners for initial approval on Jan. 10.

The Pitkin County Open Space and Trails Board voted unanimously to recommend the purchase at its meeting Thursday, Jan. 4, in Redstone.

“Snowmass Falls Ranch is quite easily the most extraordinary piece of private land in Pitkin County,” said Dale Will, acquisition and projects director for Open Space and Trails. The property was listed for sale in 2021 for $50 million though the county has been working diligently on a conservation deal since 2019. “We’ve held our breath since the property was listed, but never gave up on the hope that the ranch could be preserved,” Will said. “It will be an outstanding addition to the public lands of Pitkin County.”

Once part of the vast territory of the Ute People, the ranch was established by Danish immigrant Kate Lindvig in the early 1900s. Known as the “Cattle Queen of Snow Mass,” she assembled the land in various parcels over several years through the Homestead Act and other purchases. She continued to run the ranch as a single woman until she sold the land in 1943 to Bob Perry, his wife Ruth Brown Perry, and Ruth’s brother, D.R.C. Brown, Jr. Bob and Ruth Perry became the sole owners in the early 1950s. The ranch has remained in the Perry family for 80 years; it is now owned by a company called Perry Family Snowmass, LLC, comprised of Bob and Ruth Perry’s descendants.

Reached through the LLC’s attorney and designated spokesperson, Bart Johnson, Perry Family Snowmass offered, “The Perrys have been stewards of this special and unique property for eight decades. Not surprisingly, it is with mixed emotions that they have agreed to sell Snowmass Falls Ranch, but after careful deliberation, Perry Family Snowmass, LLC has decided that Pitkin County is the right buyer at the right time.”

The purchase price for Snowmass Falls Ranch far eclipses any other open space acquisition in the history of the county’s Open Space and Trails program, noted Gary Tennenbaum, program director. It is double the cost of the purchase of about 845 acres at the heart of Sky Mountain Park, acquired for $17 million in 2010. Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO), the Town of Snowmass Village, City of Aspen and private donors contributed to the Sky Mountain purchase, bringing the county’s contribution down to roughly $11 million.

“Fortunately, we are in an opportune position to make this purchase happen right now,” Tennenbaum said. The Open Space program has $34 million in its fund balance.

“In 2020, the BOCC and Open Space and Trails Board had the vision to issue bonds for the remaining $20 million in borrowing capacity that had been previously authorized by voters,” Tennenbaum said. Interest rates were historically low in 2020 and, with the county’s excellent credit, the program received a premium on the bond, netting over $24 million. The bonds helped provide the capacity to complete this legacy acquisition, he said.

At their Jan. 10 meeting, county commissioners will also work on setting the Open Space and Trails fund mill levy. They will have to balance the desire for property tax relief with the reality of providing future capacity for the program. There are yet more properties that have open space values to acquire, and trail projects to complete, throughout the county, Tennenbaum said.

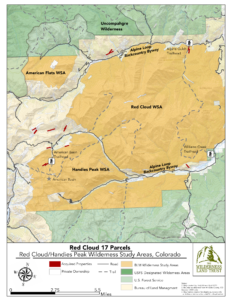

The Open Space program has applied for a 3-year, $10 million loan from GOCO to assist with the Snowmass Falls purchase and ultimately hopes to transfer much of the property for inclusion in the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness Area. Much of the ranch has a wilderness designation overlay, but since it remains private property, none of the wilderness protections apply. The county will be working with The Wilderness Land Trust and the Forest Service to determine how much of the property can be transferred and how much of the purchase price can be recouped by Pitkin County.

Snowmass Falls Ranch already provides a key portal to the wilderness area. Both the Snowmass Lake Trail and West Snowmass Trail cross through the property on easements that Lindvig deeded to the national forest in 1933.

The ranch encompasses two miles of the glacial valley located west of Snowmass Village. It is filled with aspen meadows, beaver ponds and trout streams at the foot of the high peaks of the Elk Mountains. Five meadows are irrigated with the most senior water rights on Snowmass Creek and, tucked out of view, is Snowmass Falls – the feature that gives the ranch its name. It’s one of two waterfalls on the property.

“Seeing this extraordinary property protected from further development under public ownership has been a long-standing goal of The Wilderness Land Trust,” said Brad Borst, Land Trust president. “We are delighted to partner with Pitkin County with the hopes of ultimately adding this critical wildlife habitat and public trails to the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness.”

A parcel containing five off-grid cabins – the only developments made to the ranch in the Perrys’ long stewardship – could be carved out of the rest of the ranch. It’s possible the piece could be sold, but with a conservation easement in place to establish parameters for its use and further development, Tennenbaum said.

In the short term, improvements to the existing Snowmass Lake trailhead, just outside of the ranch gate, could be made using flat ground just inside the ranch, Tennenbaum said. The current trailhead parking area lacks a functional design and is frequently at capacity.

“We hope to transfer most of the ranch to the Forest Service as soon as possible, but for now, this amazing property will be open space,” Tennenbaum said. “It’s an incredible asset but also a huge responsibility.

“The ranch remains private property until this potential transaction is consummated, Tennenbaum added. “We trust the public will respect private property during the interim period.”

On Tennenbaum’s recommendation, the Open Space and Trails Board decided the property will be closed to the public when the county takes ownership, while Open Space and Trails works on an interim plan for its management.

Contacts: Gary Tennenbaum | Open Space and Trails director | gary.tennenbaum@pitkincounty.com | 970-920-5355

Dale Will, OST acquisition and projects director | dale.will@pitkincounty.com | 970-618-5708

For the Dinè, or Navajo, the peak is Sisnaajiní. It is one of the four corners marking the boundary of the Dinetah, the traditional Dinè homeland, along with three other sacred mountains— Dibé Nitsaa in the north (Hesperus Mountain in the La Plata Mountain range of Colorado), Doko’o’osliid in the west (Humphrey Peak in the San Francisco Peaks of Northern Arizona), and Tsoodzil in the south (Mt. Taylor Peak, west of Albuquerque, New Mexico).

For the Dinè, or Navajo, the peak is Sisnaajiní. It is one of the four corners marking the boundary of the Dinetah, the traditional Dinè homeland, along with three other sacred mountains— Dibé Nitsaa in the north (Hesperus Mountain in the La Plata Mountain range of Colorado), Doko’o’osliid in the west (Humphrey Peak in the San Francisco Peaks of Northern Arizona), and Tsoodzil in the south (Mt. Taylor Peak, west of Albuquerque, New Mexico).

October Wilderness Book Club Pick:

October Wilderness Book Club Pick: